Meaning

In the post on emotional hospitality, I mentioned that emotions can give us helpful information about how we’re navigating our life tasks. Unlike emotions and their attendant life circumstances, with which we must simply be patient because we sometimes have little control, life tasks involve choice and values—things for which we can take responsibility because we have quite a bit of control. As Viktor Frankl, a famous existential psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor, wrote, “human freedom is not a “‘freedom from’ but a ‘freedom to’—a freedom to accept responsibility.” (p. 52). To be sure, there are many things we cannot be “free from,” like bodily needs, mortality, human relationships and interdependence, etc.

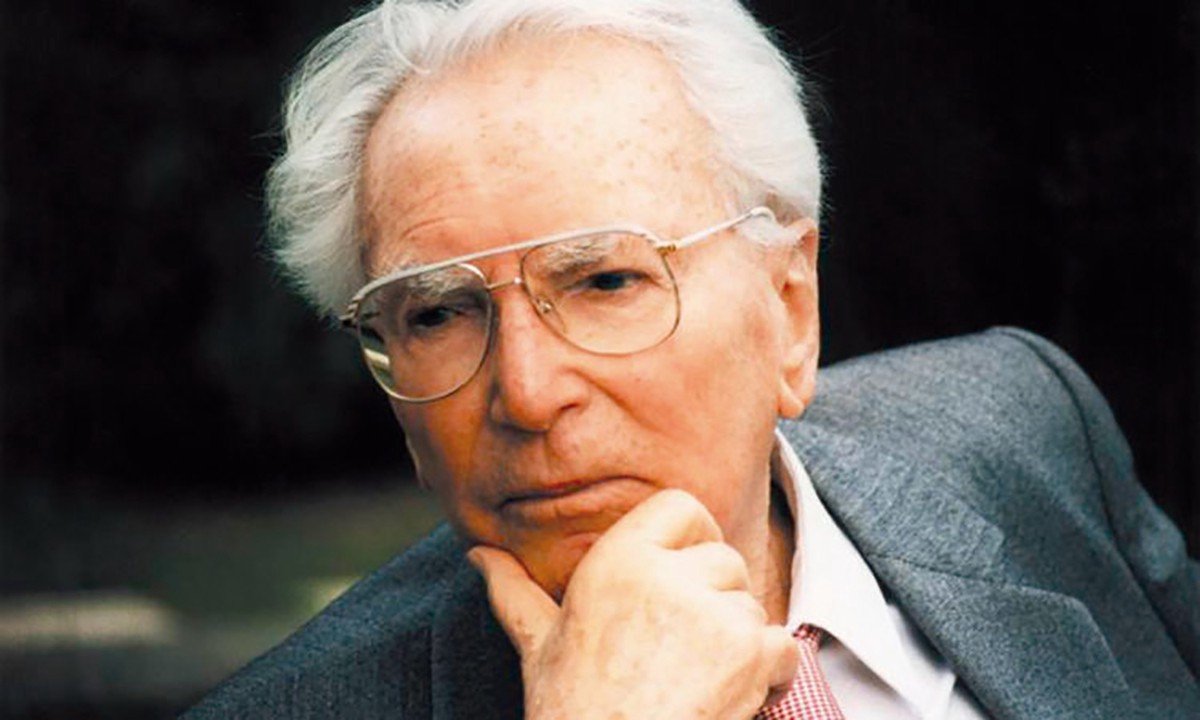

Human freedom is not a ‘freedom from’ but a ‘freedom to’—a freedom to accept responsibility.

Viktor E. Frankl, Holocaust survivor and psychotherapist

From his experiences in a Nazi concentration camp (Described in Man’s Search for Meaning—highly recommended), Frankl knew better than most that cruel circumstances fortunately do not define who we are. In this sense, the most important thing in a human life is not freedom from things that cause suffering; rather, meaning in a human life comes from how we use our freedom to take responsibility over our choices and life tasks in spite of suffering. In short, if we want to live good lives, we must take responsibility over what is in our control, no matter how much remains outside of our control. Frankl saw fellow prisoners literally die days after giving up on meaning. For his part, Frankl attributed his ability to survive the horrors of the camp to his enduring mission to publish his book, titled in English, The Doctor and the Soul. Following is an excerpt:

We venture to say that nothing is more likely to help a person overcome or endure objective difficulties or subjective troubles than the consciousness of having a task in life…. Having such a task makes the person irreplaceable and gives his life the value of uniqueness. In view of the task quality of life, it logically follows that life becomes all the more meaningful the more difficult it gets. A natural analogy is the attitude of the true athlete. The athlete sets up his problem in such a way that he may prove himself by its conquest…. Shall we not also test our mettle and grow in courage and strength through the difficulties in ordinary life? (p. 54)

Life tasks are chosen, not begrudgingly put up with.

If we take responsibility for our life tasks, our goals and values will abide (and mature) with us, while emotions continue to come and go. If we don’t have clear life tasks to anchor us and give us purpose, our emotions may feel chaotic and dissonant, because they don’t have anything solid to tether to or consistent to track on. On the other hand, when we manage to harmonize choices with values, our whole beings will hum with joy (Frankl, p. 40), like musical instruments. Thus, this is not a one and done kind of deal; it’s a daily practice. We all must strive to hone our skill at playing our unique instruments in the symphony of our families, friends, and communities.

So what is your life task(s)? If you’re not sure, that’s OK, but remember, it’s ultimately up to you to decide—life tasks are chosen, not begrudgingly put up with. Nevertheless, you might start by thinking about the circumstances that have been thrust upon you. In Frankl’s story, for example, his mission to publish his book and disseminate his approach to therapy (called “logotherapy”) developed, in part, as a response to psychological insights he gained from his own experiences and watching others in the concentration camp. His was a singular life task under extreme circumstances, but you might have several life tasks under circumstances less dire.

According to the psychiatrist Alfred Adler, a predecessor of Frankl and younger contemporary of Freud, there are a handful of primary life tasks. Adler originally set forth three tasks: the love task (deep intimacy and vulnerability with another person, including sexual intimacy), the social task (a sense of belonging and cooperation with others), and the work task (contributing something of value to your community). Later Adlerians added two more: the task of self (understanding and connecting to yourself) and spirituality (a sense of meaning and purpose in relation to something greater than yourself). You’ll notice that making money and getting power aren’t on this list. That’s because those are only good things insofar as you have enough of them to achieve these other five tasks. They are not good or meaningful in and of themselves, and that may explain why true joy is so difficult to experience for those who prioritize attaining money and power above all else.

One final tip from Dr. Frankl: “Love enormously increases receptivity to the fullness of values: The gates to the whole universe of values are, as it were, thrown open” (p. 133). Love is not an emotion per se, even though it can be associated with complex emotional dynamics. Unlike basic emotions including anger, fear, sadness, happiness, disgust, and surprise, which help you interpret experiences in light of your values, love could be called a prime value that helps you identify other more specific values. To return to our metaphor, love is like having an excellent ear in music, detecting the off notes and savoring the sweet ones. With that we have a somewhat fuller picture: Activities become meaningful “life tasks” when they are carried out in the furtherance of values, and when emotions work in terms of values that are congruent with love, you will be capable of feeling true, deep joy. In other words, with love you can train yourself to make choices that resonate meaningfully with your values.

Reference

Frankl, V. E. (1986). The doctor and the soul: From psychotherapy to logotherapy (3rd, expanded ed.). Vintage Books.